News Updates

- Benefits of Integrating Patient Engagement with Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in New Medical Product Development: A Call for Action

- Drug Shortages in the Global South: A Proposed Parallel Tech and Reg Transfer Framework

- Fair Pay for Patient Engagement: Navigating the Evolving Landscape of Remuneration

- Industry’s Window to Express Interest in Africa Continental Product Evaluation Pilot Closes End of February 2024

- Accelerating Adoption of eLabeling in Singapore: One Company’s Journey

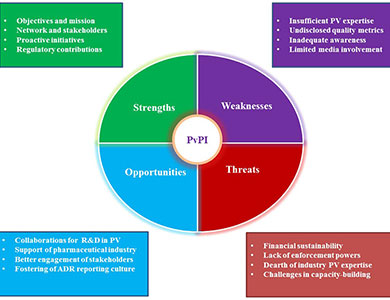

Pharmacovigilance Programme of India: SWOT Analysis

Introduction

Introduction

In recent years, pharmacovigilance (PV) has become a high priority, growing public health concern worldwide. India, for its part, has accumulated noteworthy accomplishments since the inception of the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI). India’s initiatives in PV date back to 1986, when an official Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) monitoring system

involving 12 regional centres was set up; this was followed by the identification of six regional centres for ADR monitoring in 1989. These early PV environments were complicated and did not stand the test of time. However, India’s 1997 enrollment as a member of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Programme for International Drug Monitoring helped India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) launch the National Pharmacovigilance

Programme (NPP) in 2004. Unfortunately, due to its lack of broad and forward-looking objectives, along with the absence of continuous funding from WHO, the NPP never grew beyond its budding stage.

Realizing the need for the NPP, the CDSCO in collaboration with the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) established in July 2010 the well-structured and now highly-participative PvPI and companion long-term policy. In April 2011, the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission (IPC) took over as the National Coordinating Centre (NCC) for PvPI. Against this backdrop, this article aims to judiciously perform a SWOT analysis of PVPI as it is today.

Strengths

The core strengths of PvPI are its stages of building the concept, objectives and awareness, which in turn strengthen the collation and interpretation of reports. The active, steady progress of PvPI from 2011 helped India to opt out from the list of countries where PV is at its infancy. PvPI relentlessly collects, collates and analyzes the data, recommends regulatory interventions, and communicates risks to health care professionals (HCPs) and the public. PvPI has collaborated with numerous medical colleges and hospitals, which function as ADR Monitoring Centres (AMCs) for collecting and forwarding suspected ADR reports to NCC. PvPI is in the continuous process of enrolling as many medical schools and centres of public health programmes as AMCs as possible. It is remarkable that India became the first Asian country to report over 100,000 Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs) to VigiFlow, the web-based PV system of the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMS). As of December 2016, PvPI has collected over 200,000 ADR reports. Furthermore, CDSCO closely works with PvPI with the understanding that pharmacovigilance plays a specialized, pivotal role in ensuring ongoing safety of medicinal products in India, and seeks NCC input before making regulatory decisions.Key PvPI milestones include providing a toll-free number for consumers and HCPs to report suspected ADRs, a revolutionary mobile application for reporting suspected ADRs, adverse event reporting forms in regional languages, a mandate for the pharmaceutical industry to submit reports in XML-E2B (Extensible Mark-up Language) format, and the launch of the Benefit-Risk Assessment Cell.

PvPI is quite well-networked with its various stakeholders. The support of CDSCO and PvPI’s collaboration with the industry, academia, HCPs, consumers, governmental bodies, statutory councils and professional associations to promote ADR reporting as a common practice has been a key reason behind PvPI’s progress thus far. PvPI’s active collaboration with the Indian Medical Association (IMA), which represents over 360,000 medical practitioners across the country, is significant, as the IMA has started to sensitize its members about the significance and methodology of reporting ADRs to PvPI. The fact that the presence of a PV Cell has been made a prerequisite for any medical school to be approved by the Medical Council of India (MCI) has played a key role in strengthening the structure of PvPI. Similarly, ADR reporting by corporate hospitals is mandated for them to maintain accreditation from the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (NABH).

Weaknesses

As PvPI is positioned only as a data collection programme and not as a competent authority, the roles and defined responsibilities of PvPI and India’s regulatory agency CDSCO are not well-differentiated. Even though PvPI performs all major PV-related activities, it does not in practicality go beyond making recommendations and issuing office orders; we must note that PvPI lacks enforcement powers. Even in governmental gazette notifications pertaining to PV, the programme is not mentioned. Despite PvPI’s strong networks with various stakeholders, effective coordination between and within these networks is not evident. PvPI staff and advisors are generally from academic backgrounds and do not have much industry experience. Although UMC is involved in training PvPI team members, there is a gap in PvPI’s understanding of established global regulatory PV practices which could be bridged by enhancing PvPI’s dialogue with seasoned authorities like the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the US FDA.PvPI has received a good number of ADR reports. But, when seen in the context of the country’s population, the number indicates a very low ADR reporting rate. Measures taken by PvPI to improve the available resources are moderately inadequate at best, and efforts to bring awareness to the public, physicians and other stakeholders have not yet reached all who may be impacted, mainly due to the esoteric outlook of the programme. For PvPI, there is a pressing need to develop an India-specific database rather than fully relying on UMC’s VigiBase. The performance of the programme varies across AMCs throughout the country, with ways and means of qualitative and quantitative monitoring not firmly established. There remains a paucity of evidence for the effectiveness of PvPI initiatives like the toll-free number, mobile application, etc. It is questionable whether approaching physicians through Continuing Medical Education (CME) programmes will make PV interesting for them, instead of addressing reasons for them to not report ADRs to PvPI.

Other than ADR reporting, there is little opportunity for free and open communication between the public and PvPI. PvPI has yet to procedurally assess the status of knowledge, attitude and practice of PV activities by all its professional stakeholders. Although PvPI maintains mass media and social media presence, meaningful two-way communication still needs improvement.

Opportunities

The progress of PvPI has attracted various stakeholders to actively participate in enhancing the Indian PV system. Research and development initiatives by the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) and the Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI) have considerable impact on the growth of PvPI. PvPI aims to optimize drug safety through prescient research and has asked ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) institutions to submit proposals for enhancing PV research. The scope of PV, which is currently restricted to ADR data collection and analysis, is also soon expected to include pharmacogenomics as a part of the scientific component of PvPI. It is remarkable that nearly 100 pharmaceutical companies joined hands with CDSCO and PvPI to frame guidelines for good PV practices in India, anticipated for 2017 release.As expected, the spectrum of PV capabilities available in India has expanded thanks to the growth of the PV outsourcing industry in India. The need remains for interlinking the thinking of various stakeholders who could devise an integrated, multidisciplinary PV approach. The symbiosis of the myriad talents available in the Indian pharmaceutical industry, professional bodies, academia and all other healthcare sectors, with the CDSCO/PvPI, under a common cause, will be fruitful and could pave the way towards harmonization and capacity building in the discipline. IPC is closely working with PCI (Pharmacy Council of India) to bring pharmacovigilance into the pharmacy curriculum. CDSCO has also established an advisory committee to engage community pharmacists in PvPI.

IPC has assured the representation of nursing professionals in various panels under PvPI. Orientation courses on PV must be conducted for drug inspectors who can double as aggressive ambassadors for drug safety. Professional associations such as the Indian Society for Clinical Research (ISCR) have been proactively vocal in offering their support to the PvPI through their PV Council. This two-way communication between PvPI and statutory councils, professional societies, groups with mandates and industry associations, could sort out various problems in integrating the flow of ADRs from various sources. There is a need for linking socio-political, socio-cultural and ethical elements in the PV system which will expressively support the Government of India in promoting PvPI as an independent entity and in establishing a dedicated PV institute (possibly named the “Indian Institute of Pharmacovigilance” or IIP) central to the entire discipline. The fact that IPC is in the process of being recognized as the first WHO Collaborating Centre for Safety of Medicines and Vaccines in SouthEast Asia hints at a long-term possibility for India to become a PV leader in this region.

Threats

As a public health programme under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare of the Government of India, the financial pressure faced by PvPI needs much consideration. AMCs are provided with technical, administrative, and financial support by PvPI. As PvPI is continuously expanding through the enrollment of new AMCs, there is a need for improved funding and transparent agenda over the flow, control and utilization of funds. It is also necessary to redefine and differentiate the roles, responsibilities, and limitations of PvPI so that existing dilemmas (such as dual power centres and consequent challenges like dual reporting of ADRs by industry to CDSCO and PvPI) are sorted out.As an interdisciplinary field, pharmacovigilance requires diverse skill sets. Lack of global expertise is a major threat. PvPI has the responsibility of identifying and bringing into its arena experts holding industry experience to close this skill gap. It is essential to keep the PvPI working team updated with international drug safety legislation and established PV practices. Even though industry experts are involved in an advisory capacity, the current PvPI system does not allow industry expertise to be a part of its steering committee or its working group; as a result, decisions made by PvPI appear to be derived from theory rather than practice. The expertise of participants in PvPI’s Signal Review Panel (SRP) must be clarified, and the involvement of industry personnel is much needed in SRP because industry signal detection capabilities are more mature. As PvPI intends to conduct advanced training for AMC personnel to increase health care professionals’ awareness of ADR reporting, the relative inadequacy of professional PV trainers in PvPI makes little sense. It is necessary to realize that practicing clinicians and teaching pharmacologists may not be PV experts.

Although awareness lectures, public campaigns, conferences, workshops, post-training reminders such as periodic eMails and mobile message alerts were attempted, recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that more than 50% of health care professionals were not aware of PvPI and 55% of the population answered incorrectly about the existence of PvPI in India. Similar research conducted in 90 ADR monitoring centres working under PvPI highlights that 68% of the doctors, 80% of nurses and 81% of the pharmacists, are unaware of PvPI in India. Although 71.3% were interested in reporting suspected ADRs, 67% did not know where to obtain ADR reporting forms. Contributing factors for underreporting include fear of legal liability, lethargy, diffidence, insecurity, overwork, and lack of financial incentives and time; these remind us to reconsider approaches to nurturing drug safety practices among health care professionals.

Conclusion

India is expected to be the sixth largest pharmaceutical market by 2020. It is necessary to implement prescient actions because the expected flow of data and reports will be too large to be handled with current available resources. In a populous country like India, establishing and running a drug safety program without execution powers is not justifiable. Therefore, the need to modify bureaucratic decisions to pave way for public-private partnerships which will in turn bring global PV experts into PVPI is compelling. PvPI must ensure the participation and commitment of all states in the country towards drug safety. This is vital. In several states, some institutions are either not actively participating or not completely aware of the objectives of PvPI. PvPI should analyse this problem in these institutions and provide feasible solutions to achieve meaningful results. The fact that PvPI staff are beginning to be recruited through third-party private agencies raises questions of job security, which, in turn, raises fears that PV professionals may not consider working for PvPI to be an attractive career choice. However, opening up contract opportunities for positions with higher responsibilities within PvPI could bring in industry-trained PV professionals whose global experience can greatly benefit the Indian populace.PvPI can be said to be at crossroads in its journey towards idealizing the drug safety system in India and has to deduce workable methodologies to remain financially viable, structurally strong and functionally successful, while rendering translational effects in public health.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge colleagues Dr. Vignesh Rajendran and Ms. Kokila Ramamoorthy, both Pharmacovigilance Associates at Oviya MedSafe, for their support in authoring this article.References available upon request.